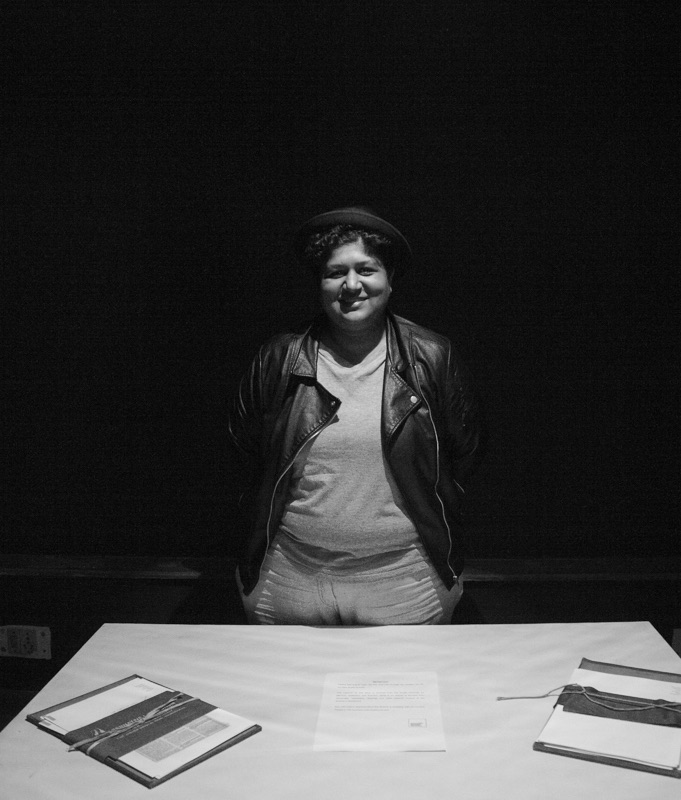

PECHAKUCHA NOTES – Sumitra Sunder

On November 11, 2021, we were delighted with our second members’ PechaKucha. Four members were chosen through an open call to discuss their current and recent curatorial projects in the form of PechaKucha presentations: 20 slides are presented while a presenter has 20 seconds to comment on each slide, for a total presentation of 6 minutes and 40 seconds.

You can now follow the selection of these contributions in our blog section.

A Glimpse into Curatorial Practice in South India – Call for Curators PechaKucha

November 11, 2021

This article is based on the PechaKucha style talk delivered on November 11 for Call for Curators.

To look at the various kinds of curatorial practice in Southern India, this presentation looks at some work that I have been part of and some of the projects that I have led. First, the Kochi-Muziris Biennale (KMB). This large-scale recurring exhibition happens in Fort Kochi of Kerala in India. The first edition of this show was in 2014, following which there have been four editions all led by artist-curators. The crux of this show is that the curator is a practicing artist and since its inception it has become a landmark for contemporary art in the country.

[1. Kochi_muziris Biennale Logo, Aspinwall House, Kochi, Kerala. 2016. Image credit – Sumitra Sunder.]

One unique aspect of the KMB is the Students’ Biennale, which is an art education initiative of the Foundation that runs the exhibition. This is a one-of-a-kind, student-centric exhibition that showcases the work of art school students from government supported art schools in India. The 2016 edition saw 15 curators work together with colleges to show the work of over 400 students. The venues were unused warehouses in the Mattanchery area of Fort Kochi, abandoned temple sites and other ‘found spaces’ that were selected by the Foundation. Over a year of work went into this show, which began in November 2015.

[2. Students’ Biennale Curators, Mattanchery, Kochi, Kerala. November 2015. Image credit – Sumitra Sunder.]

The works you see here are made by the students of the College of Fine Art, Bangalore and Chamarajendra Academy of Visual Art, Mysore in Southern India (Karnataka). Each of the students engaged with one aspect of “public”, the stem of which I will get into shortly. The students are Chathuri Nissansala, Partha Banik and Munira Diwan. Chathuri’s work reflects her experience as a woman in urban India, while Munira explores the violence of genital mutilation which is still practised among the Bohri Muslims in the country. Partha was reflecting on the idea of rest and migration in the city and used discarded rubble to make a bed. These works are a result of a series of workshops and interventions conducted in Bangalore in 2016.

[3. Display of Chathuri Nissansala’s work ‘Queen’ at Students Biennale, Mohammed Ali Warehouse, Mattanchery, Kochi, Kerala. December 2016. Image credit – Sumitra Sunder-]

[4. Display of Partha Banik’s work at Students Biennale, Mohammed Ali Warehouse, Mattanchery, Kochi, Kerala. December 2016. Image credit – Sumitra Sunder]

The workshops were conducted in the summer of 2016, some months before the exhibition in Fort Kochi. These workshops were the result of my collaboration with spaces like the Alternative Law Forum and Maraa, a media collective in Bangalore. I will speak about the Public Space concerns of Maraa shortly. This specific image is from a conversation with Raghu Wodeyar who runs a collective for young performance artists in the city. During this session the students were able to discuss the significance of public art practice as well as the artists’ experience of performing. This collective concerns itself with the larger ecological crisis facing large metropolises in South Asia.

[5. Workshop with Artist Raghu Wodeyar, Venkatappa Art Gallery, Bengaluru. June-July 2016. Image credit – Sumitra Sunder.]

One of the students at the College of Fine Art created a piece of public performance art at a local art fair in the winter of 2015. This immediately followed a conversation about access to art and its inherent value. A student called Anusha prepared a large flex sheet to be laid on the main road leading to and around the fair. This fair, called Chitra Santhe which means art market in Kannada, is an annual event supported by the Karnataka Chitrakala Parishath, which also houses the college of fine art. The work involved requesting that people walk on the flex sheet after applying paint to the soles of their feet or shoes. It was a comment on the much talked about ‘footfall’ that large art fairs and exhibitions consider important.

[6. Installation_So you think you know the closet, Khirkee Studios, New Delhi, 2018. Image Credit – Nayantara Gurung Kakshapati.]

This image is from a workshop with a collective called Maraa. The word means tree in Kannada and the collective has been concerned with the city of Bangalore. Civic liberties, urban displacement and the ecological crisis have been at the forefront of their activism. In this workshop, the collective took students through the idea of private and public. This was conducted in one of the last few public spaces in the city, Cubbon Park. In our contemporary times of losing access to public space, especially for minority communities, this was a big part of my curatorial framework for the Students’ Biennale.

[7. Dissemination Materials, So You Think You Know The Closet, Khirkee Studios, 2018. Image Source – QAMRA archive.]

From this point on I will be speaking about some of my personal work with queer archives and curating. “So you think you know the closet” was a project born from an intensive look at the queer archive. What gets recorded? Can the public be shown the ugly face of a Police State and what does that do to queer people? This was the focus. Interrogation rooms in police stations do not lend a cozy feeling. By making this space as stark as possible with no “comfortable” seating or environment, people are forced to witness the discomfort of the closet. A projection of statements culled from archival material adds severity to the experience.

[8. Newspaper Clipping – Installation material, So You Think You Know The Closet, Khirkee Studios, 2018. Image Source – QAMRA Archive.]

Newspapers report suicides very frequently, but there is more to news of a lesbian couple committing suicide in peri-urban India. One must read the fine print and infer that these may have been honour killings, and that there is a larger social problem with respect to violence against queer lives. Some of these people did take their lives, but the root cause is a society that does not want to allow queer people to live full lives. The State still does not recognise gay marriage. The material from the archives also points towards something urgent – the need to document queer lives as the last time people fought for the repeal of section 377, the queer community was labelled a minuscule minority and therefore, not important. This need to archive comes from the experience of not having any real records in the public domain of queerness.

[9. Pride March – Installation material, So You Think You Know The Closet, Khirkee Studios, 2018. Image Source – QAMRA archive.]

What stemmed from this curated installation? Conversations with other curators based in Karachi and Kathmandu led to the beginnings of “Queer Records.” This South Asian collaboration engages the queer archive. Pegging the focus on language, especially the language of the colonised, was a way to read the archive. Going back to the installation “So You Think You Know the Closet?”, the material on display was from QAMRA – a queer archive for memory, reflection, and activism. This archive is based in Bangalore, where most of my work is located. QAMRA was initiated to serve as an aid to the legal battle for the queer community. Using material in this archive led to a substantial change in my curatorial practice, it prompted a move from engagement with just art and artists to displaying the archive.