Meet CFC Member Lívia Nolasco-Rózsás: exploring information technology

#CFC Members Program #Lívia Nolasco-Rózsás #MembersCFC Members Spotlight is a bi-monthly interview series showcasing the work of our members on our blog and social media. Through this feature, we highlight the diverse curatorial practices in our community and encourage new connections and exchange.

Meet CFC Member Lívia Nolasco-Rózsás

Lívia Nolasco-Rózsás’s curatorial, research and writing practice is defined by an interdisciplinary approach to the arts, its media and its relation to the sciences and information technology. She has worked together with institutions such as the ZKM | Karlsruhe, Centre Pompidou, Paris, Nam June Paik Art Center, or Ludwig Museum Budapest.

We recently interviewed Lívia Nolasco-Rózsás to learn more about her curatorial journey, inspirations, and insights into the art world.

CFC: What inspired you to pursue a career as a curator? Was there a particular moment or experience that sparked your interest?

LNR: In 2005, Peter Weibel had a solo exhibition at the Kunsthalle Budapest titled A nyitott mű / Das offene Werk. The exhibition had a profound effect on me, similar to the transformative impact described by Rilke in his sonnet about the archaic Apollo torso. The sculpture, damaged by centuries and left incomplete (or rather, “open”), seems to call out to the viewer: “Du mußt dein Leben ändern” (“You must change your life”).

My perception of art—and what I considered to be art—was fundamentally altered after experiencing this exhibition. Ten years later, when I began working at the ZKM | Karlsruhe, a professional dream came true. The ZKM’s reputation as a pioneering art institution, where one can engage with cutting-edge research on the intersection of art, technology, and society, was particularly appealing to young professionals like me. We were eager to explore the impact of new and mass media, as well as information technology, on art and our cultures, and to make these reflections accessible through thematic exhibitions, publications, and digital tools.

CFC: What thread or idea ties your work together?

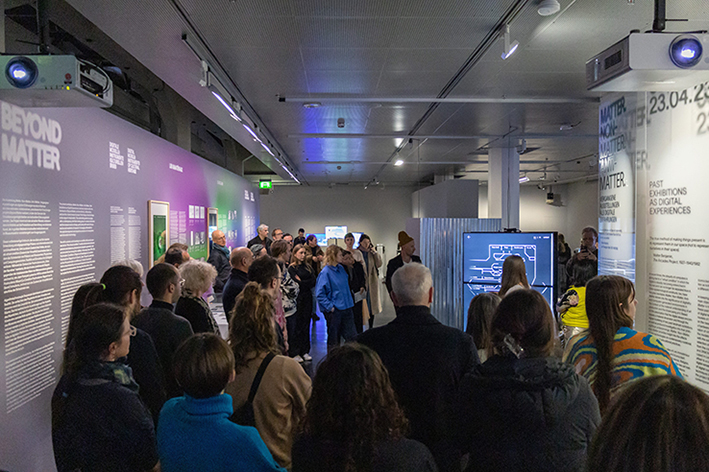

LNR: I’ve been focusing on the impact of computation on contemporary art and the socio-political phenomena brought about by information technology. Had the chance to initiate and develop thematic exhibitions in collaboration with esteemed colleagues, raising questions on topical issues such as electronic surveillance and democracy (Global Control and Censorship, 2015-18, with Bernhard Serexhe), the genealogy and social impact of planetary computation and computer code (Open Codes, 2017-21, with Peter Weibel et al.), the notion of computer-generated space (Spatial Affairs, 2021-23, with Giulia Bini), the impact of digital technologies on materiality and synchronicity (Matter. Non-Matter. Anti-Matter, with Marcella Lista et. al.), the social and political implications of immersion (Immerse!, 2023, with Corina Apostol), and digital world-making, exploring the influence of science and computation (ARE YOU FOR REAL, 2023-34, with Giulia Bini).

CFC: Name a project or exhibition that holds special significance for you. What made it stand out?

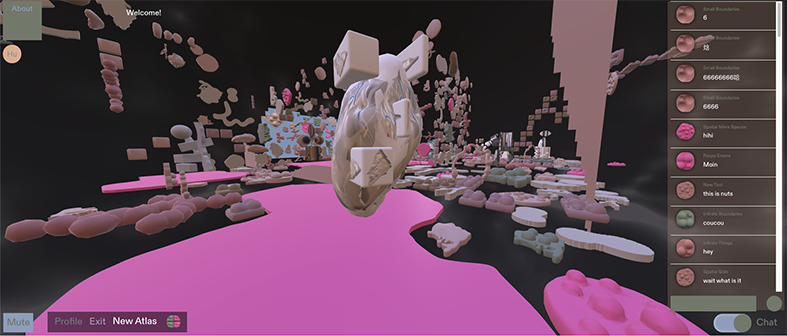

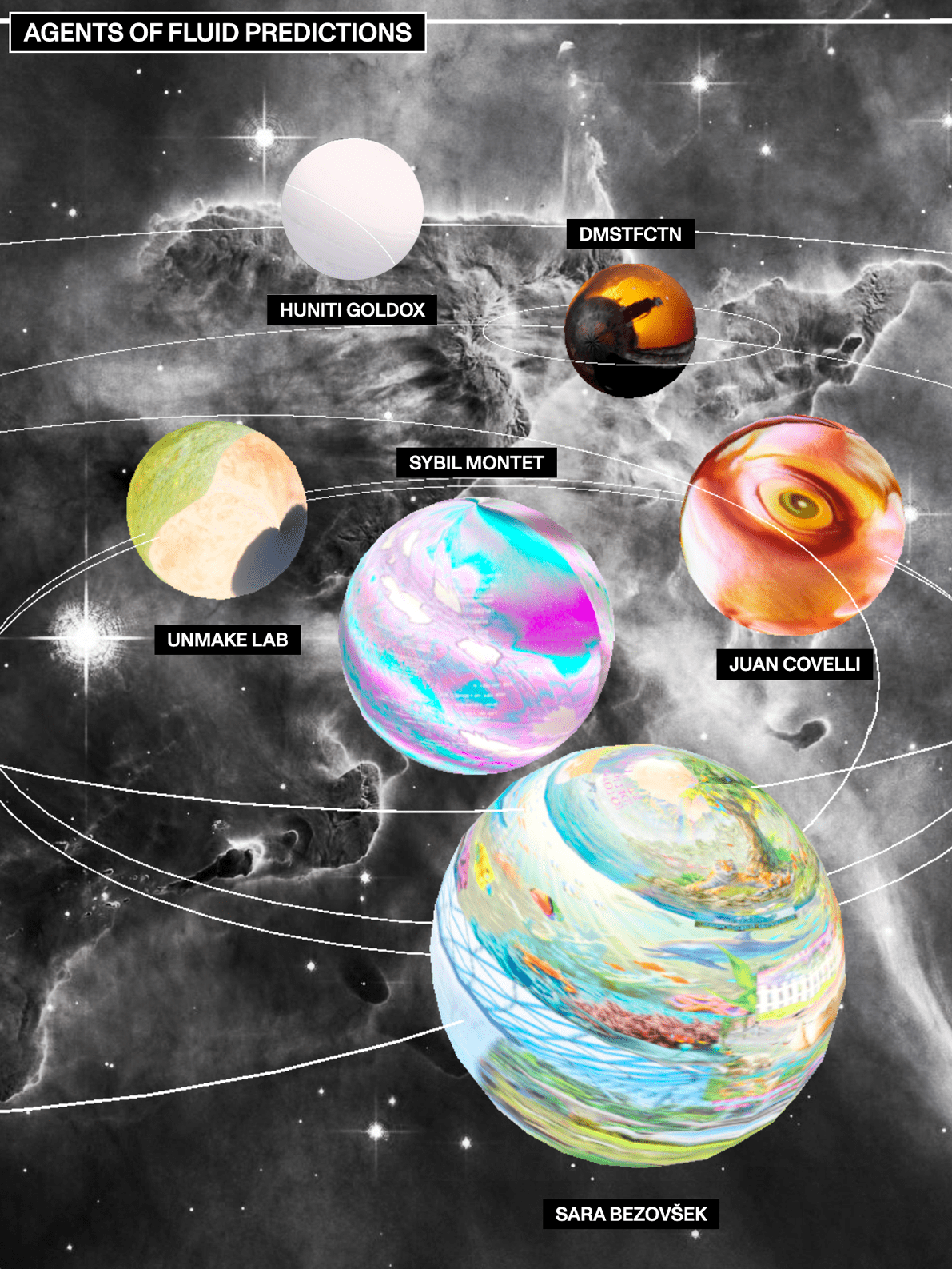

LNR: It is always the latest, or the ongoing that seems the most significant, even if some previous might have been more significant in terms of space, resonance, or number of actors involved. Currently I work, together with Giulia Bini, on a hybrid exhibition, called ARE YOU FOR REAL. It is a currently online platform for investigating how computation and the sciences relate to reality—the full potential of their roles in generating new worlds—through the work of artists.

They use computers as tools, as collaborators, and as agents of world creation. They increasingly base their works on the results of scientific research, while also borrowing and transforming its methods in their investigations.

ARE YOU FOR REAL aspires to situate and question a multiplicity of cosmotechnics (to pick up Yuk Hui’s term) shaped by a diverse and decentralized community of artists through a sequence of cosmological propositions, alternating between planetary and terrestrial, ecological and technological, magical and decolonial. They enable us to grasp various aspects of digitalization, and to explore a reality now irreducibly entangled with the online sphere.

The project will have further physical manifestations. Until now certain details of the whole were presented in form of pop-up shows, screenings and discussions at the Seoul Museum of Art, at HKW Berlin, at HEK’s Mesh Festival in Basel. From next year further, more extensive presentations, in form of actual exhibitions are to be expected, thus digital world-building will manifest in a tangible way.

CFC: What’s your favorite part about being a curator? And, if you don’t mind sharing, what’s the most challenging?

LNR: The favorites include: Having the opportunity to construct worlds through exhibitions that don’t impose but accommodate a variety of thoughts and actions. Creating conditions to nurture ideas, always in collaboration with like-minded peers whenever possible. Disrupting the monotony of linear time (and reminding myself and others that it doesn’t exist). Being constantly confronted with the ephemerality of ourselves and our art.

Challenges: Balancing between digital and physical objects. Engaging with dissipating audiences who aren’t fewer, just less visible, less present, less tangible. Overcoming distance and language barriers, staying open, and maintaining the ability to address both intellectual and emotional needs, without neglecting sensitization. Contributing to manifestations (in the spirit of Jean-Francois Lyotard) and Gedankenausstellungen (thought exhibitions, akin to those of Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel). Helping audiences form connections with interpretable objects and offering a platform for knowledge to emerge from these interpretations.

CFC: Any hot takes on the current state of the curatorial field or the art world in general? What do we need more or less of?

LNR: I am not deeply immersed in the art world but follow segments of museums and cultural NGOs in the countries where I currently live (UK) and where I have previously lived or worked, for longer or shorter periods of time, including Germany, Switzerland, Mexico, Colombia, South Korea, China, Czech Republic, and Hungary. My experience is limited, but I observe that patronizing attitudes toward cultural discourse, cancel culture, and censorship driven by political agendas may shift the focus of cultural engagement. This could lead to a greater emphasis on personal truths rather than the pursuit of shared metaphors. Such fragmented realities often result in cognitive dissonance, confusion, and a lack of coherent frameworks to discern fact from fiction. A mindset that embraces doubt as an integral part of the search for knowledge is essential for true cognition.

CFC: What advice would you give to aspiring curators just starting their careers?

LNR: Curating is a means, and the curatorial is a method, for achieving specific goals—such as building communities and temporary constellations of human and non-human actors, sharing knowledge, mediating research outcomes, evaluating new ideas, sensitizing audiences, and revealing phenomena and connections that might otherwise remain hidden.

I have no advice to offer; curating is the most experiential practice I have ever encountered.

Explore more of Lívia Nolasco-Rózsás‘ work on her Instagram.

Are you interested in learning more about our CFC membership? Dive into how to become a CFC member here.